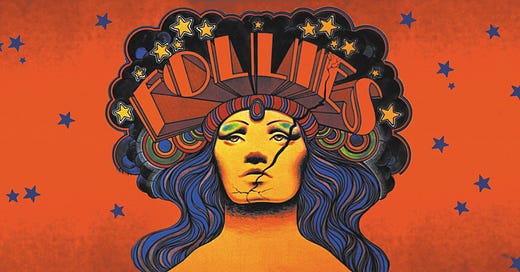

Follies: How Stephen Sondheim Brought Us The "Concept Musical"

The first musical in a long line of Sondheim and Prince collaborations that challenged how stories are told.

You can’t like musical theatre without liking Stephen Sondheim. I mean, maybe you can, but you’d be fighting an uphill battle. Widely known as one of the greatest (if not the greatest) musical theatre creators of all time, Stephen Sondheim dared to change how we hear and perceive musical theatre. With unpredictable melodies, masterful lyricism, and a lot of heart, Stephen created a legacy of masterful storytelling, crafting musicals that have become interwoven in the fabric of the art form.

Though Sondheim has so many wonderful musicals to choose from, this week I listened to Follies, Stephen’s first collaboration with Hal Prince and one of his first forays into writing music and lyrics for a project (as compared to his work on Gypsy or West Side Story, where he only wrote the lyrics).

I’ll be honest, Follies isn’t my new favorite musical, but I did learn a lot from listening to it, and I always hold a reverence for Stephen’s works. Before getting into my thoughts about the score, however, let’s examine some dramaturgical context of the show and how it was made.

If you don’t know, now you know:

When I think of Stephen Sondheim, I think of his collaboration with Hal Prince. In the same way that Lin Manuel-Miranda didn’t make Hamilton the hit musical alone (thank you Tommy Kail, Alex Lacamoire, and Andy Blankenbuehler), many of Sondheim’s greatest musicals were forged in the fires with Hal Prince.

Hal is an iconic producer and is behind classics such as Cabaret and Phantom of The Opera. Stephen and Hal had already worked together on West Side Story, but their collaboration would grow to become one of the most iconic pairings in musical theatre history. Stephen and Hal agreed to work on both Follies and Company, and through these two shows an important and revolutionary format for musical theatre was explored — the “concept musical.”

I argue that Hair was one of the first true concept musicals: an ensemble-led piece that asks us to follow a group of individuals that may or may not be interconnected through a piece, rather than focusing on one protagonist or main plot line. But Sondheim would crack open this format and push it to its limit in his career, beginning with both Company and Follies.

Follies takes place in a decaying Weismann Theater that is soon set to be demolished and turned into a parking lot. The theater used to be the home of the Weismann Follies, who are having a reunion to celebrate the past and honor the days of yore.

The reunion attendees consist of two main couples — Sally and Buddy, and Phyllis and Ben. Though these two couples take up a lot of the stage time, there are also characters such as Heidi and Carlotta that get beautiful, almost stand-alone songs that drive the action forward. The musical deals both with the characters who are returning for the reunion as well as memory versions of the characters that play in and out of the action.

Follies asks you to focus on the event of the reunion and the collective experience of the group rather than one character, and though this may be familiar to our modern minds, we must appreciate the storytelling risk it took in 1971.

Speaking of risk, Follies was a flop. It was one of the costliest shows to be mounted on Broadway as of 1971, and it didn’t return its investments. The spectacle involved in creating the show drove the costs up, and the unconventional story structure and heavy themes in the text isolated and divided audiences.

Though Follies was panned by the critics upon its debut, lets also remember that classics such as Merrily We Roll Along (which is currently selling tickets for exorbitant prices) were also flops in their times, and that box office sales are not our only indicator of quality.

My great mentor Eric Price says that there are “hits” and “flops,” and “failures” and “successes.” Terms such as “hits” and “flops” have to do with ticket sales and critical reviews, whereas “failure” and “success” has more to do with the artistic integrity of the work. After listening to Follies this week, I do feel that it is a success. Decades later, the show is still produced widely across the world and the ambitious story holds up all these years later.

Now that I have properly paid tribute to Stephen’s work, let’s dive into what makes Follies so great.

The breakdown:

Follies begins with a massive drumroll and a Prologue that immediately sets us up for the drama of the show. The orchestrations in this entire musical are brilliant, transporting us back to the day of the Ziegfeld Follies. Though this song has some singing in it, the first half effectively functions as an overture. If you’ve been reading along this year, you know how I love a good overture.

In the second half, we begin to drop into the scene and setting of the Weismann Theater, where we are introduced to the showgirls. This show mixes diegetic singing (meaning the characters know they are singing) and non-diegetic singing (the character is unaware that they are breaking out into song and the song is just a manifestation of their internal life) in a really interesting way. The nature of the setting being a theater and the characters being performers makes it easy for Sondheim to blur the lines between performance and reality.

The second number, “Don’t Look At Me,” we are introduced to Sally Durant, one of the central characters of the musical who despite being married to Buddy, still longs for her old flame Ben. Hearing this song made me breathe a sigh of relief - it is so deliciously Sondheim. Even just the opening music under Sally, this rolling orchestration is so busy yet so carefully crafted — it’s such a staple of Stephen’s. The melodies are unpredictable and the melodic lines are crafted in a way that they really mirror the emotional arc of the lyric. While this may seem like it would be intuitive for a composer/lyricist, making the lyric and music match perfectly so that the musical emphasis and verbal emphasis line up can be very challenging. Here, Stephen makes it look easy.

The third track, “Waiting For The Girls Upstairs,” holds the original title of the musical (before it was renamed Follies by Hal Prince). I thought this song was fine. It went on a little too long for me, but dramaturgically it serves the purpose of introducing the men of the story and exploring more of what the past looked like for all these characters. Much like “All I Need Is The Girl” in Gypsy, this feels like a song that could win me over when I see it staged.

Next we dive into “Ah, Paris / Broadway Baby.” While I found “Ah, Paris” to be meh, I immediately jumped when I heard “Broadway Baby.” Going into Follies I thought I only knew “Losing My Mind,” but turns out there are so many quintessential Broadway songs that I just didn’t realize were from this show! “Broadway Baby” is a classic, and I loved it.

Next comes “The Road You Didn’t Take,” another perfect Sondheim number. Songs like these make me feel as though I can watch Stephen come into himself musically. The orchestrations rumble along in the beginning, and the strings in this song so beautifully uplift the lyric and melody, tying together the song with a metaphorical bow. I love the occasional horn that he uses here!! The horn is all the same note and just clips in. It’s restrained and so well done.

I also have to take a minute to appreciate the rhyme here:

You take one road

You try one door

There isn't time for any more

One's life consists of either/or

It’s so simple, but some things need simplicity to find their best form.

Moving on, we hear another wonderful song, “In Buddy’s Eyes.” This song is delivered by Sally, who remarks about how much she loves Buddy. This song feel like if “Bill” from Showboat and “Everybody Loves Louis” from Sunday In The Park With George had a baby. I absolutely love when characters lie in songs - it lets their subtext work overtime, with the words coming out of their mouth not matching their emotional life. I feel that a lot of contemporary musical theatre works have characters just saying exactly what is on their mind, but a good actor will make a meal out of a lyric that allows room for subtext.

Next we hear “Who’s That Woman?” While I think the song itself is fine (I do love the usage of “mirror mirror on the wall” and the reframing of that classic line), this is the first song where I really feel the importance of the memory versions/past versions of the characters. It makes me feel that Follies is really about reckoning past and present and how time changes us all.

Out of “Who’s That Woman” comes the famous “I’m Still Here.” When listening to this song, I felt that this tune and “Ladies Who Lunch” are sisters. It’s interesting how much of the Sondheim canon sort of folds back in on itself in a lovely way — it’s not that he has rewritten the same songs, but rather that his canon is an exploration of characters with similar struggles and perspectives.

I also think of the Drowsy Chaperone — through the character trope of the washed up older woman may feel familiar to us, Sondheim was out here forging ground for these types of characters.

The musical arc of this song really boils down to the horns, which grow throughout the song in a really delicious way. I could listen to just the instrumental of this song and be so satisfied with its musical development.

Against the rowdy “I’m Still Here,” Stephen juxtaposes “Too Many Mornings,” a duet between Ben and Sally. This song was one of my favorites, and I have to make space to celebrate one of my favorite lyrics in the show:

Thousands of mornings

Dreaming of my girl

All that time wasted

Merely passing through

Time I could have spent

So content

Wasting time with you

The way he uses “wasting” negatively in the third line of this stanza and then recontextualizes it in the last line as a positive “wasting time with you” is so good. It reminds all of us lyricists that we have so many tools in language to play with that sit outside the domain of rhyme and scansion. Stephen is a genius when it comes to wordplay, and he hides this gem of a lyric in the greater whole of the song.

When Sally sings, “I should have worn green, I wore green the last time, the time I was happy,” I was so absolutely gutted. This song was the first time I felt myself rooting for the characters, and more specifically Sally, hoping that she would end up happy.

We love emotional investment.

While I adore “Too Many Mornings,” the next track “The Right Track” fell a little flat for me. While I was invested in Sally, I had the opposite feelings about Buddy. The problem with the concept musical is that we leave my favorite characters for too long and then I both yearn for their return and resent the characters who take up stage time in their absence.

Speaking of people singing who aren’t the main characters, we now dive into “One More Kiss,” a soprano ballad sung by Heidi and Young Heidi. It’s interesting to me how the memories almost become more powerful and more present throughout the show, before finally overtaking the story entirely. While I don’t have any emotionally investment in Heidi, I thought this song was fine. My patience for soprano ballads is thin, but this song is short and sweet (clocking in at just 2:15), so my patience was not too tested.

After wandering a bit, we return to the main plot of the couples as Phyllis debates if she could stand to leave Ben in “Could I Leave You?” This song has some biting lyrics, and the way that we get to watch Phyllis just absolutely unravel onstage is riveting. It reminds me of Rose unspooling in front of all of us in “Rose’s Turn,” except there are still five more songs to go!

I was told by incredible dramaturg é boylan last week that Follies has a cascade of endings (referring mostly to the “Loveland” ending), but I feel that in some ways “Could I Leave You?” is what starts the beginning of the end.

Speaking of endings, we now are catapulted into a dream sequence with the memories of the characters called “Loveland,” which is a sort of pastiche of songs that explore the main character’s woes and wants. First we hear “You’re Gonna Love Tomorrow / Love Will See Us Through,” a track that I felt paled in comparison to the tracks around it.

After this we hear “The-God-Why-Don’t-You-Love-Me Blues,” sung by Buddy about his relationships with Margie (previous lover) and Sally (current wife). While I felt that “The Right Girl” was meh, I liked this song a lot and felt that we got to watch Buddy more concretely confront the past.

This song (and this whole sequence) is really the culmination of the exploration of diegetic and non-diegetic singing, meaning that these songs are all performed under the guise of this greater performance in “Loveland,” with the spirit of the Follies really overtaking the musical, but the characters are still exploring their current emotional life. I love the way that Sondheim explores both these textures at once, and I don’t know that I’ve ever seen something like that before!

After Buddy’s big number, we get the heart wrenching ballad, “Losing My Mind” sung by Sally. While my feelings may change in seeing the musical, Sally was the only character who really earned my investment in my listen through, and she cashes in on my investment in this song. While Sally’s circumstances are specific, this song applies to anyone who has pined for a lover.

This lyric is why we buy a ticket to Follies:

You said you loved me, or were you just being kind? Or am I losing my mind?

Every piece of this song is perfect. The gutting lyric that is repetitive yet continues to explore the main theme, the way the orchestrations build in the last third, and of course, the incredible vocal delivered. This will be on repeat for a long time for me.

After Sally has pulled us all through the emotional mud, we hear “The Story of Lucy and Jessie,” sung by Phyllis. Lucy and Jessie are names that Phyllis has assigned to the parts of herself that are in conflict with each other, and we watch her actively try to sort out herself. I think this song is tough because it is set against “Losing My Mind,” and anything that comes after that song would have to be so good to compare. It felt like “Losing My Mind” is an 11 o’clock number, and that I was primed for the finale afterward, but forced to listen to Phyllis sing. I’d love to know why he chose the order for this cascade of endings.

Regardless, we do arrive at the end with the Finale, “Live, Laugh, Love.” Before these words hung in my southern mother’s kitchen, they were in Follies. This song is delivered by Ben, who mid-song forgets the words. This is where “Loveland” begins to break, just as the characters themselves break. It’s a parallel of theatrical form and internal life of the characters, which is so interesting.

Unusually, the musical doesn’t have a closing musical number, but rather, ends with book as the setting of “Loveland” dissolves and we return to the Weismann Theater. It ends with the couples trying to patch things up. Without reading the script, I don’t know that I can properly comment on how the show ends, but I will say that I felt the most important and effective song toward the end of the show was “Losing My Mind,” and that everything after felt a little extraneous. Not that I think the show should end there, but that was certainly the climax of my emotional listening experience.

Some parting wisdom:

While Follies may not be my new favorite musical, I can certainly appreciate what it did for the theatrical form and the evolution of the concept musical. It brought together Hal Prince and Stephen Sondheim to solidify their lifelong collaboration, and it brought us incredible tracks such as “I’m Still Here,” and “Losing My Mind.” Through the show may not be perfect, nothing is, and it certainly has left a lasting impact on me.

In staging, I’m so curious to see how the younger/memory versions of the characters are used. While their importance is certainly upheld in the songs, I know that seeing it all unfold would make me so much more certain of their function in the story. There is something so delightful about a physical manifestation of memory and the past and our ability to confront previous versions of ourselves, and I think that Follies uses this concept really well.

Speaking of concept, I just have to circle back to the way that this story used unconventional structure really effectively. Musical theatre is a really young art form in comparison to other forms such as classical music or even straight theatre, and so writers have a lot less precedent of what works. This is exciting because we can watch the canon evolve over the span of just a few lifetimes, with each generation learning from the last and improving the form. Follies is an example of how Stephen Sondheim raised the bar for all musicals, and musicals like A Chorus Line, Cats, and Working all stand on its shoulders.

Though I loved listening to the music in this score (the horns win my MVP award), it is a gift any day to listen to Stephen’s wordplay and rhyme which continue to take my breath away with every listen. I can’t wait to explore more of his canon this year.

Speaking of more Substack content:

Next week I will be listening to another show that I have been told for years I need to know (yes, I know, this is the theme of the whole Substack).

It’s time for me to finally get into Once.

The girl with the guitar in me is so ready.

More next week, and happy listening.